Hejduk's Hidden Room

Year | 2020

Status | Idea, Academic (Harvard GSD Core I)

Instructor | Max Kuo

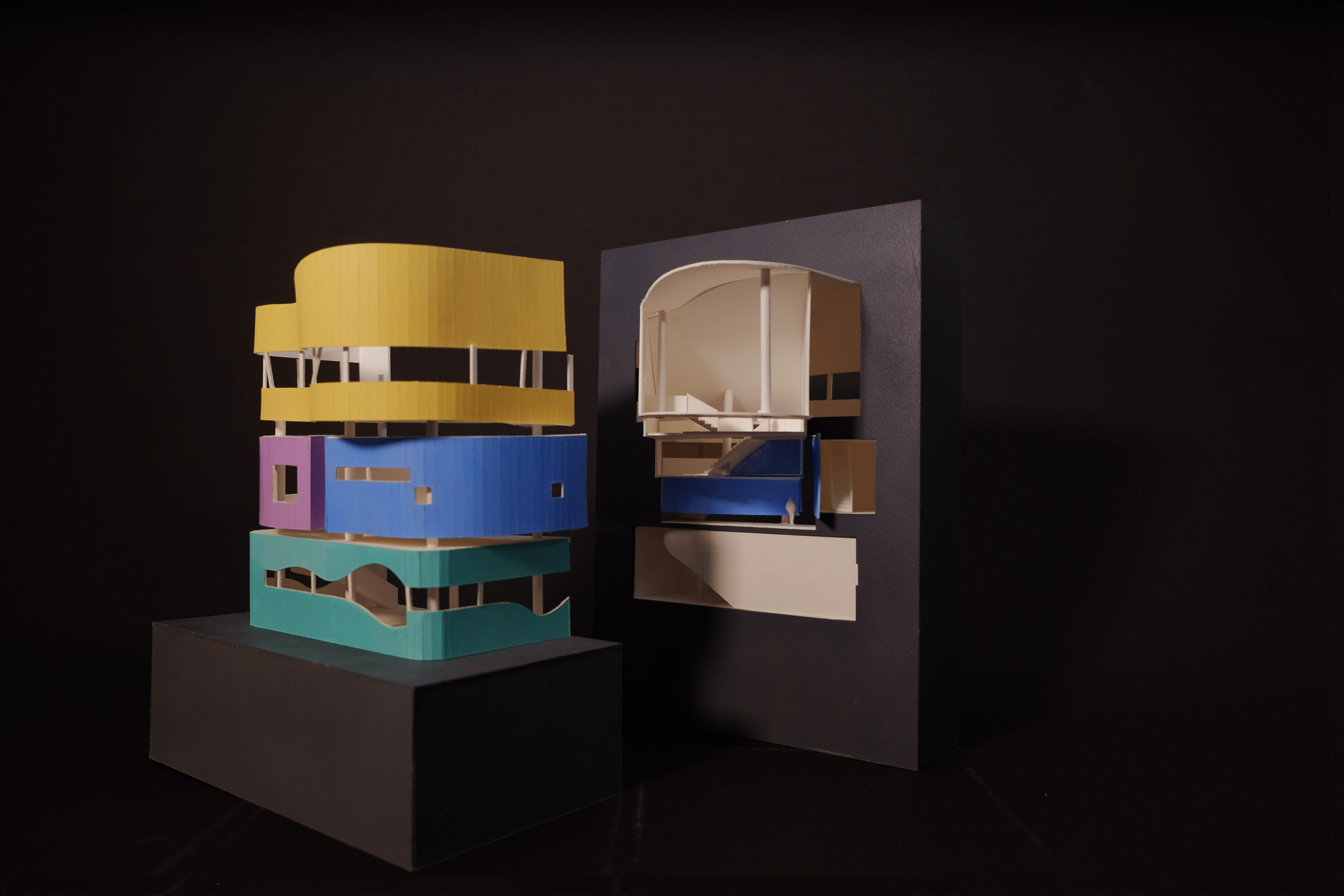

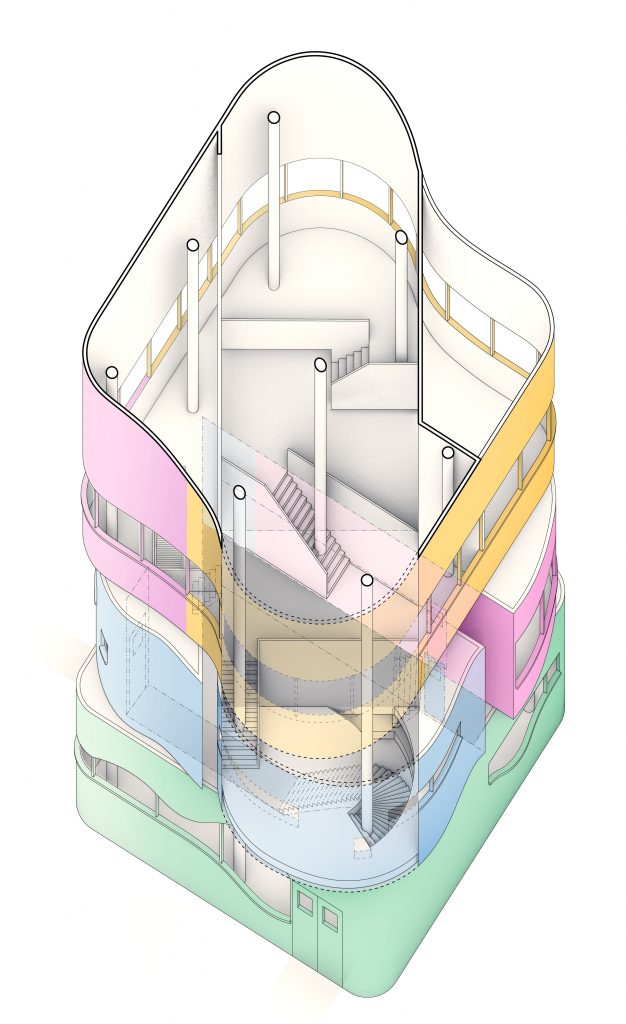

Designed by John Hejduk in 1973, Wall House II explores the relationship between publicness and hiddenness through the introduction of a Wall. Referencing cubist still-life paintings, the Wall conceals auxiliary spaces beyond the ‘picture plane’ while accentuating the resident’s passage between rooms. The result is a house which, from the front, appears as four individually-coloured biomorphic volumes floating against a large grey Wall. While it suggests that there are four rooms, an examination of the floor plans betray the fact that there are only three, begging the question – where is the fourth room?

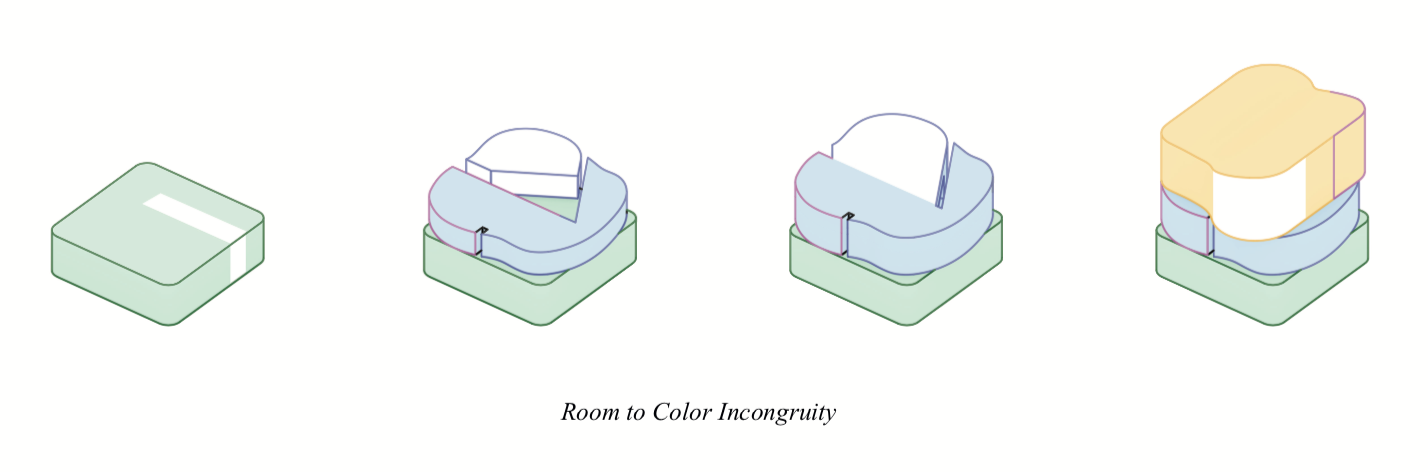

By lifting the Wall, the ‘picture plane’ is removed and the three rooms in front of the Wall are allowed to complete themselves. Rigorously following formal signifiers employed by Hejduk, a pill-like hidden room is discovered.

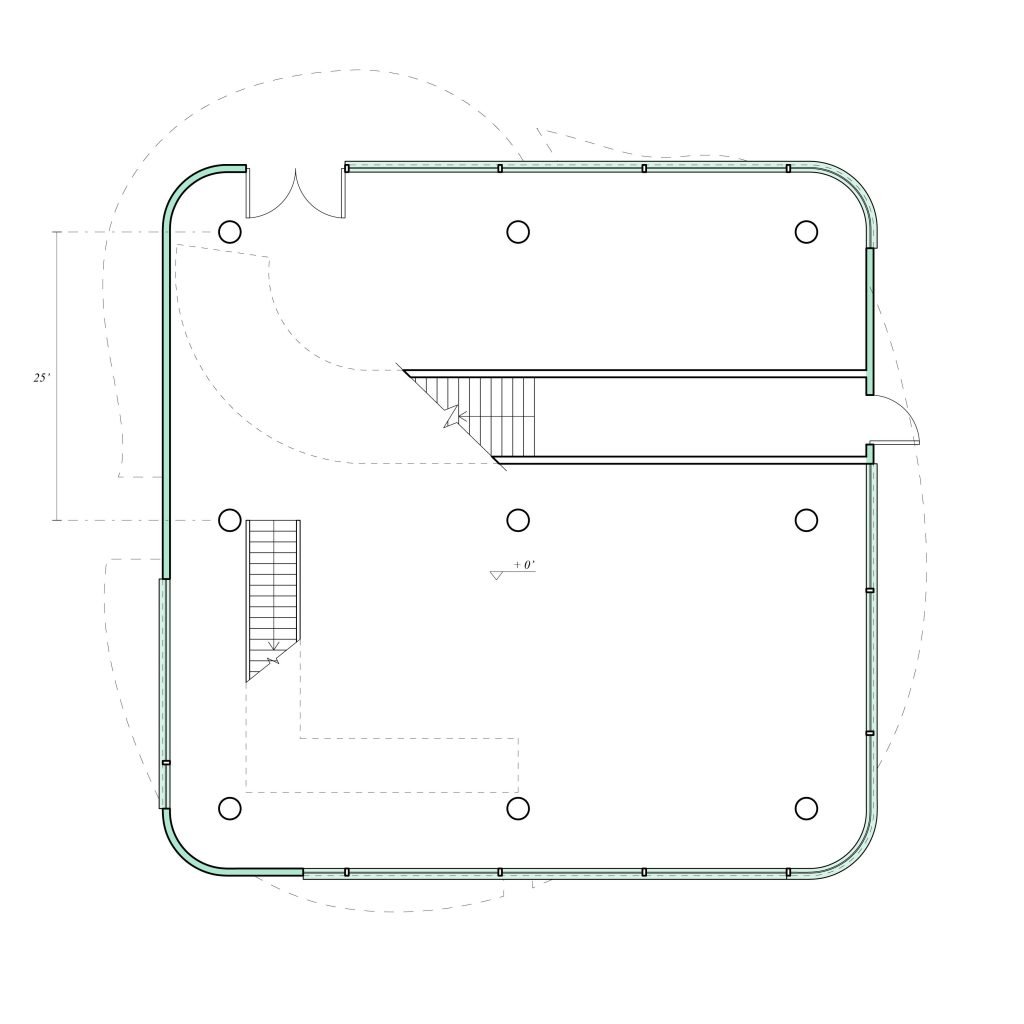

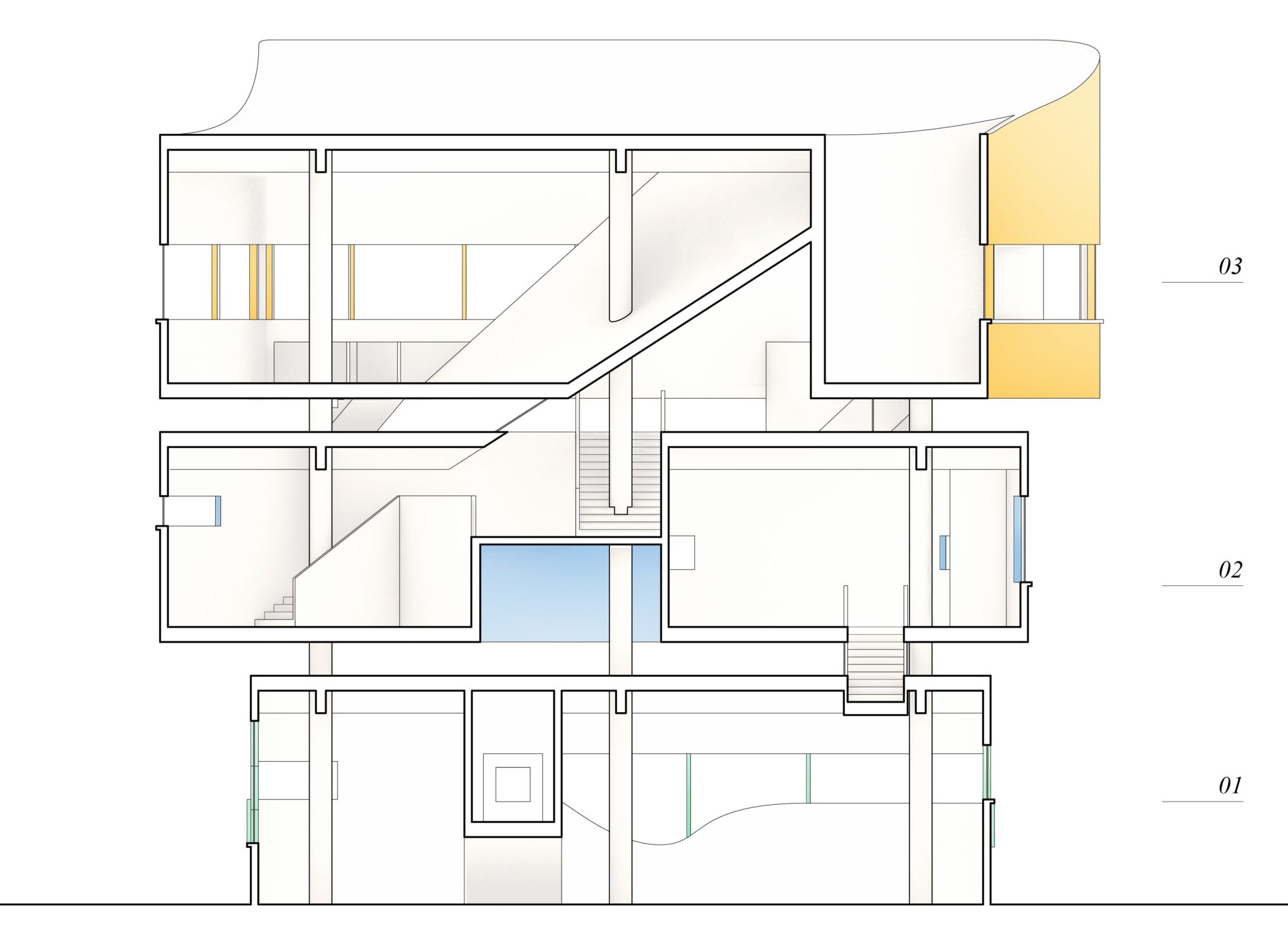

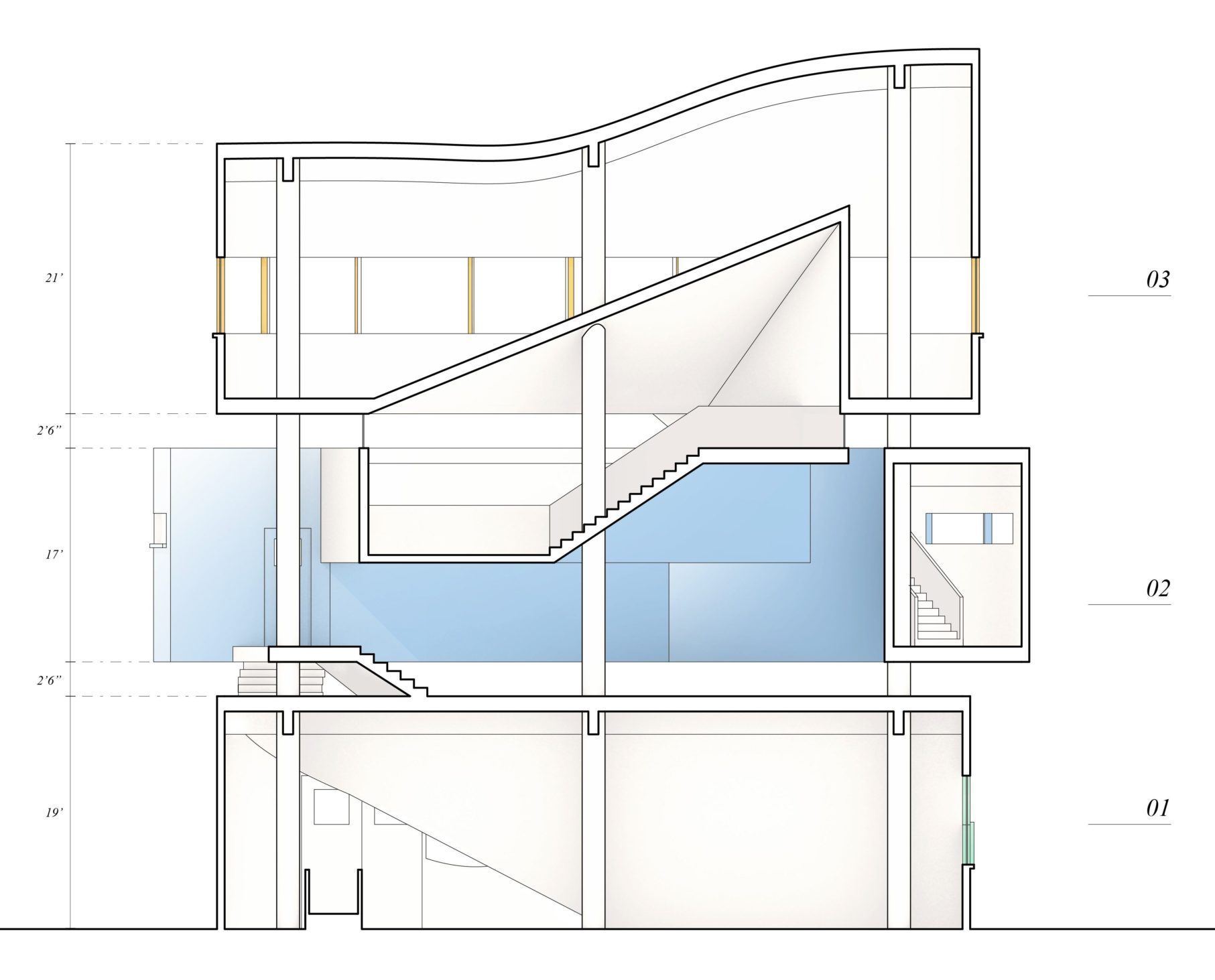

The ground floor of Wall House II was deceptively simple, it was a rectangle with rounded edges. Its banality is essential and in the hidden room, it becomes even more bland; it becomes a directionless square with rounded edges.

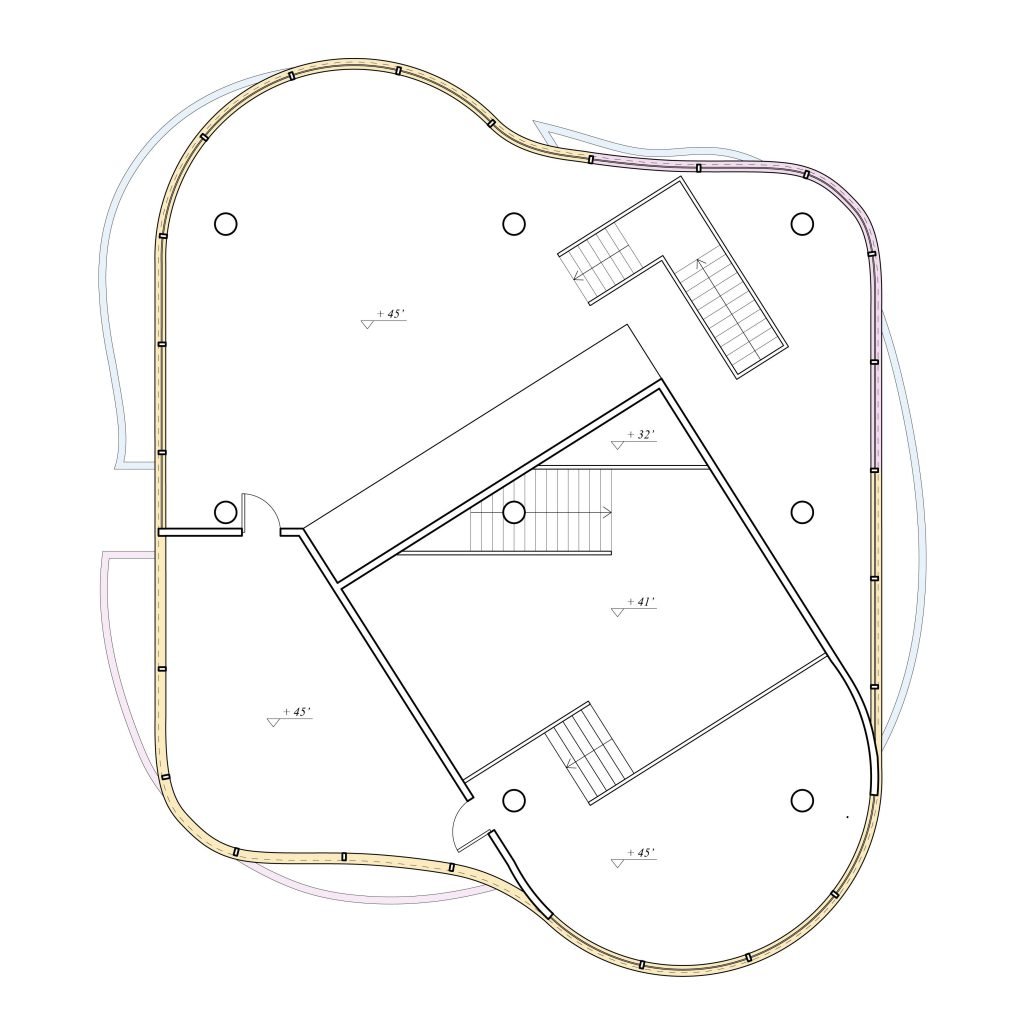

The top floor of the Wall House was a continuous, sinuous curve that bulges out from the planometric geometry of the ground floor. By the simple act of mirroring its plan, the hidden room project makes it clear that this floor is related to the ground floor. It becomes a bloated twin of the ground floor, as if the ground floor swallowed a pill-like geometry. The diagonality and implied momentum of the pill geometry echoes George Braque’s Studio III, a painting Hejduk looked at frequently during the design of the Wall House. In the painting, a bird shatters a wall. Here, the bird is reincarnated as the pill, leaping out from the ‘Wall’ that once defined the Wall House.

The pill is the hidden room.

While there is no longer a ‘Wall’, the disruptive role that the ‘Wall’ once played is now executed by the pill. Rather than an autonomous object, the pill interacts with the surrounding objects, directing and determining how the rest of Hejduk’s forms are experienced.

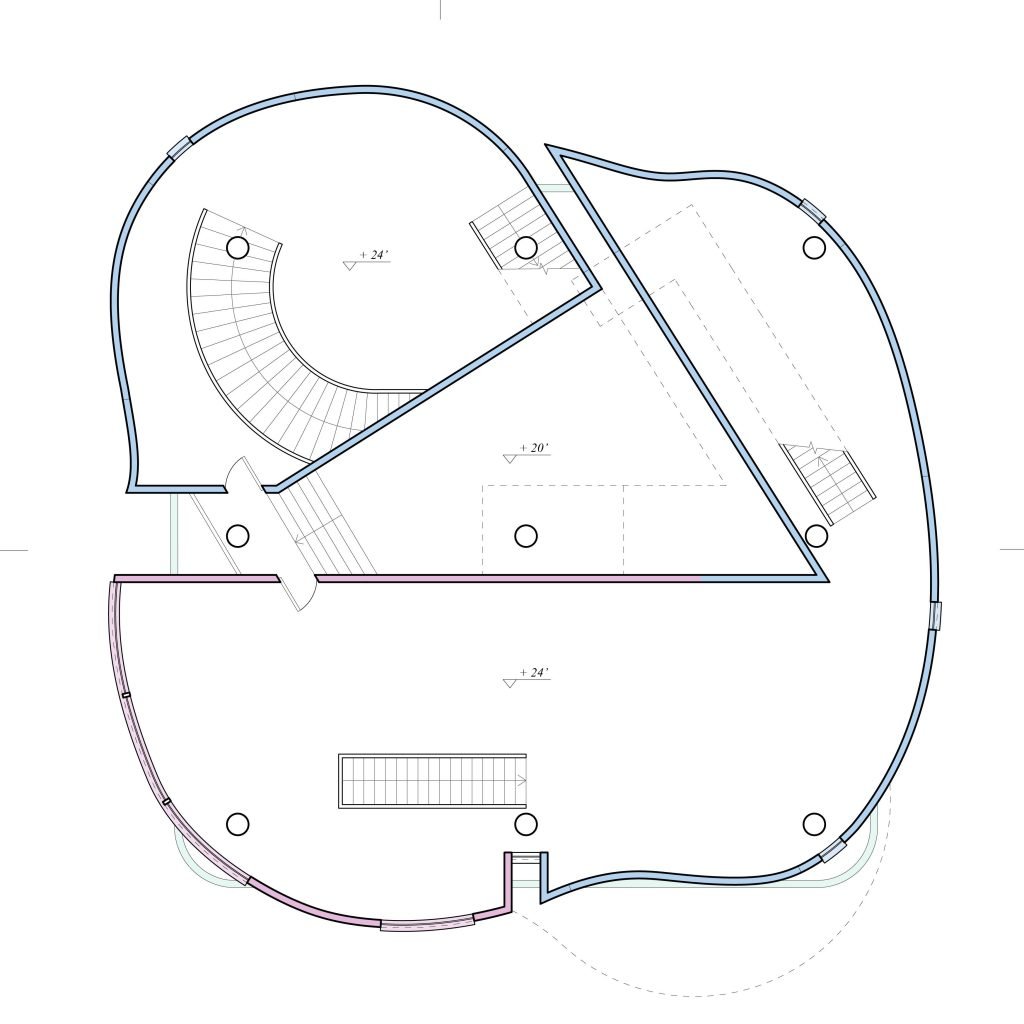

The exterior and interior spaces of Hejduk’s second floor were incongruous. From the exterior, it appeared as two volumes, but there is actually only one volume notched in the middle.

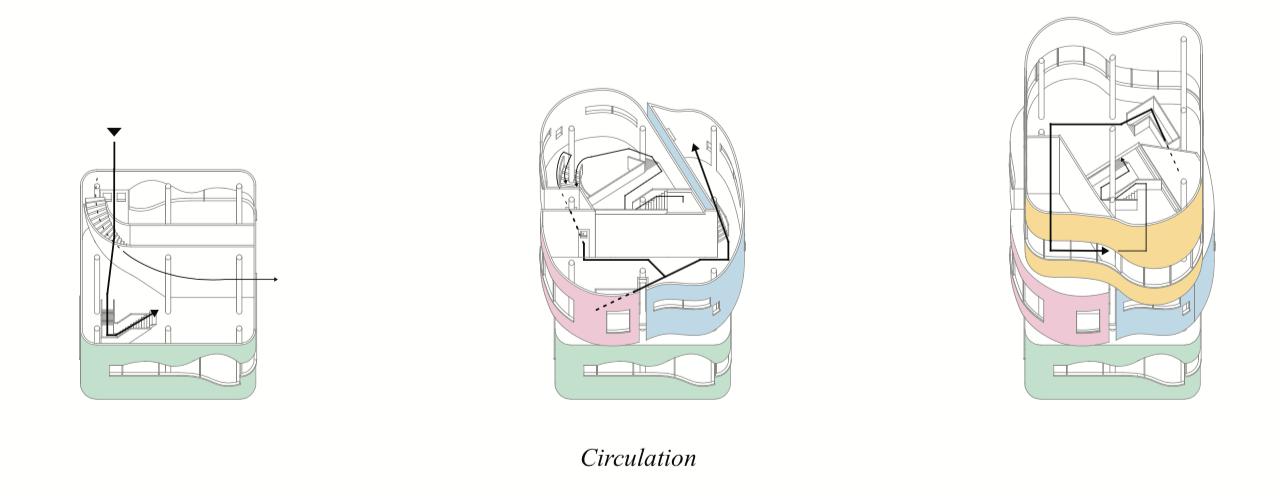

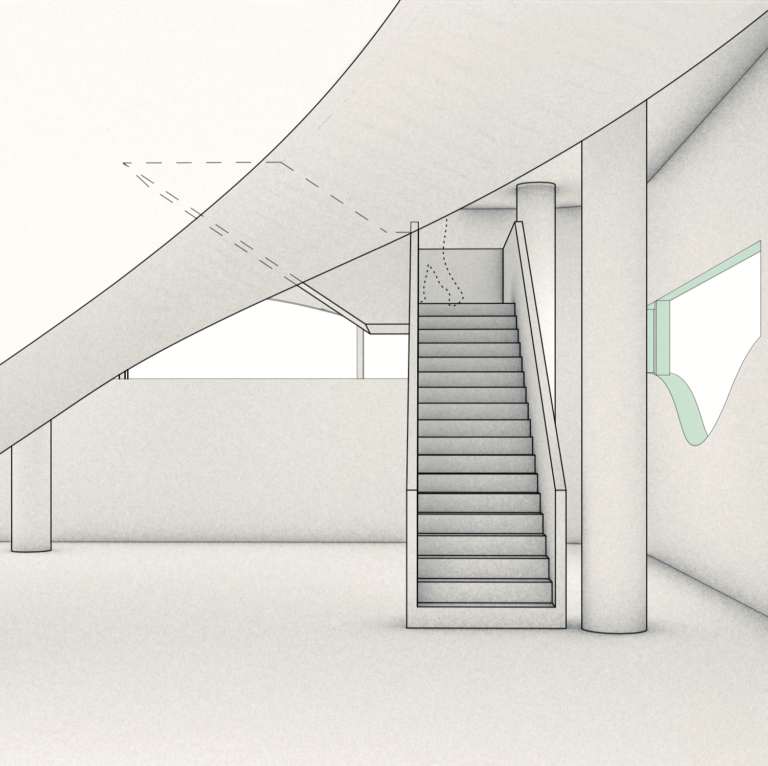

Hejduk designed the small notch on the second floor facade as a window while perfectly aligning it with a column. The contradiction between view and obstruction becomes a motif in the completed form as the pill volume traverses from the third floor down to the second floor with a series of staircases and platforms. Rather than columns obstructing views, columns obstruct circulation. All staircases in the pill are perfectly aligned to the centre of columns. The hidden room reinforces its defiance from the rest of the building through its insistence on disrupting circulation. This constant interruption enforces a tension reminiscent of the ‘Wall’, which was the Wall House’s moment of greatest repose and tension.

On the second floor, the pill-shaped hidden room begins to contort in preparation to conform to the predictable nature of the ground floor. By the time it reaches the ground floor, the hidden room is in alignment with the column grid, appearing as nothing more than a fire-staircase.

During the involution of the pill, a phantom of the ‘Wall’ reappears. Between this wall and the pill, Hejduk’s second floor notch is exaggerated and an outdoor space emerges. Where the solidity of the ‘Wall’ once acted as the transition between rooms, voids have taken over.

As a result, the hidden room is nested within what is perceived as the original forms of the Wall House. Hejduk’s corporeal still-life geometries have been freed from the ‘picture plane’ to take in all its world-making capacities.

In other words, the Wall House is no longer a cubist still-life painting, it has become a cubist world.